Communicating with an alien species, reteaching concepts like the meaning of “I” and “you,” making a friend—there are countless selfish and selfless motivations for overcoming a language barrier. But in the five examples below, from a Shakespeare retelling to an interstellar war story that’s equal parts sci-fi and fantasy, these characters discover that building common ground through language creates its own surprising intimacy.

Miranda and Caliban by Jacqueline Carey

Though Miranda’s father, the sorcerer Prospero, is able to summon the “wild boy” who lurks outside into their palace with a spell, he cannot use the same magical arts to force young Caliban to speak. It’s Miranda, with a gentle patience in direct contrast to Prospero’s frustrated haste, who first draws Caliban’s name from where he had hidden it deep within himself. By literally getting down to Caliban’s level, Miranda helps him slowly recover the words that he had lost after trauma, stitching together smaller words into loftier ideas about God and death and the magical spirits bound on the island on which they are the only human inhabitants. It is through this repetition of “sun” and “good” and “sun is good” that Caliban begins voicing thoughts like “Miranda is sun”—a compliment, she recognizes, but a dangerous one. When Prospero threatens to remove Caliban’s free will as punishment for not fully cooperating with his questions, Miranda must use their fledgling shared language, or even just her frightened tears for her new friend, to keep Caliban safe. And as they grow together in the decade or more before the events of William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Caliban comes to have the opportunity to return the favor…

Though Miranda’s father, the sorcerer Prospero, is able to summon the “wild boy” who lurks outside into their palace with a spell, he cannot use the same magical arts to force young Caliban to speak. It’s Miranda, with a gentle patience in direct contrast to Prospero’s frustrated haste, who first draws Caliban’s name from where he had hidden it deep within himself. By literally getting down to Caliban’s level, Miranda helps him slowly recover the words that he had lost after trauma, stitching together smaller words into loftier ideas about God and death and the magical spirits bound on the island on which they are the only human inhabitants. It is through this repetition of “sun” and “good” and “sun is good” that Caliban begins voicing thoughts like “Miranda is sun”—a compliment, she recognizes, but a dangerous one. When Prospero threatens to remove Caliban’s free will as punishment for not fully cooperating with his questions, Miranda must use their fledgling shared language, or even just her frightened tears for her new friend, to keep Caliban safe. And as they grow together in the decade or more before the events of William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, Caliban comes to have the opportunity to return the favor…

Babel-17 by Samuel R. Delany

Babel-17 is a novel about language. It specifically digs into the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which is the idea that until you have a word for a concept, you are incapable of having the concept itself. In the book, Babel-17 is the name for a language which doesn’t allow for the concept of I, which means that people who speak it literally have no conception of themselves as individuals. It also rewrites your thought as you learn it, and programs you to become a terrorist without your knowledge.

Babel-17 is a novel about language. It specifically digs into the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which is the idea that until you have a word for a concept, you are incapable of having the concept itself. In the book, Babel-17 is the name for a language which doesn’t allow for the concept of I, which means that people who speak it literally have no conception of themselves as individuals. It also rewrites your thought as you learn it, and programs you to become a terrorist without your knowledge.

Where love comes into it is the relationship between Rydra Wong, a space captain and poet who is charged with investigating the code, and The Butcher, a man suspected of terrorism. The Butcher has amnesia. No one has any idea where he came from or what language he originally spoke, but now he has no concept of “I” or “you”—instead beating his chest when he needs to indicate himself, and refer to others by their full names:

“Don’t you see? Sometimes you want to say things, and you’re missing an idea to make them with, and missing a word to make the idea with. In the beginning was the word. That’s how somebody tried to explain it once. Until something is named, it doesn’t exist. And it’s something the brain needs to have exist, otherwise you wouldn’t have to beat your chest, or strike your fist on your palm. The brain wants it to exist. Let me teach it the word.”

Rydra spends half the book trying to overcome this block and teach him not just the word “I” but also a sense of self, and the two have a long, twisty conversation as he switches back and forth between calling himself “you” and calling Rydra “I” before he begins to get the hang of it, and this dissolves the barriers between them so completely that they’re in love before they even realize it.

“Story of Your Life” by Ted Chiang

While Ted Chiang’s novella is about first contact with an alien species whose written and oral languages resemble nothing that has ever come from the human mouth or hand, the language barrier is less about the one between linguist Dr. Louise Banks and the alien heptapods, than her own barriers with fellow human Dr. Ian Donnelly. (Spoilers follow for both the novella and the film it inspired, Arrival.) Attaining fluency in Heptapod B radically alters how Louise thinks, as it allows her to see time not as a linear construct but as something happening simultaneously—another example of Sapir-Whorf at play. On the one hand, this fills her with incredible empathy for how the heptapods regard space travel, death, and the future of their species—but the true intimacy she discovers is with Ian, who has been learning the language alongside her. Because his communications with the heptapods more concern mathematics, he does not reach the same level of fluency in Heptapod B, and therefore does not know, as Louise does, that they will fall in love and have a daughter who will someday die far too young.

While Ted Chiang’s novella is about first contact with an alien species whose written and oral languages resemble nothing that has ever come from the human mouth or hand, the language barrier is less about the one between linguist Dr. Louise Banks and the alien heptapods, than her own barriers with fellow human Dr. Ian Donnelly. (Spoilers follow for both the novella and the film it inspired, Arrival.) Attaining fluency in Heptapod B radically alters how Louise thinks, as it allows her to see time not as a linear construct but as something happening simultaneously—another example of Sapir-Whorf at play. On the one hand, this fills her with incredible empathy for how the heptapods regard space travel, death, and the future of their species—but the true intimacy she discovers is with Ian, who has been learning the language alongside her. Because his communications with the heptapods more concern mathematics, he does not reach the same level of fluency in Heptapod B, and therefore does not know, as Louise does, that they will fall in love and have a daughter who will someday die far too young.

The intimacy is somewhat one-sided, not unlike the love story in Audrey Niffenegger’s The Time Traveler’s Wife, when one party knows how the romance will end but spares the other that knowledge, in the hopes of not affecting their free will. For Louise, their falling in love is a foregone conclusion, which perhaps is what allows her to do so in the first place.

The Little Mermaid

Disney’s version of The Little Mermaid is actually quite interesting in terms of how communication between Ariel and Eric fosters love. Initially, Eric is besotted with the underwater princess after she rescues him from certain drowning and sings to him as he wakes. Her voice is the thing that immediately draws Eric to her—so much so that he cannot recognize her as the woman who saved his life when she washes up on shore again without her voice. (Sure, it seems unlikely, but it’s a cartoon, okay? Suspension of disbelief is key.) Though he thinks his mystery woman is gone forever, he lets Ariel stay at his palace to heal up, and she communicates to him as best she can through gestures, expressions, and activities. Even though he’s still holding out for that incredible voice, he starts to fall for her all the same, bit by bit. It’s only with Ursula’s magic that the sea witch can use Ariel’s stolen voice to trap Eric for her own. Once the spell is broken, Eric is lucky enough to find that the mysterious voice on the shore and the woman he’s been falling in love with in spite of himself are one and the same person. The language of music brought them together, but it was the absence of spoken words that strengthened their bond.

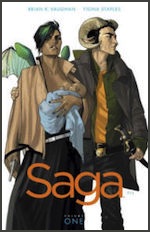

Saga by Brian K. Vaughan and Fiona Staples

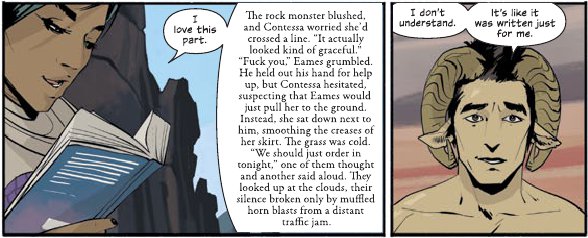

It’s no surprise that soldiers Marko and Alana fall in love over a romance novel, considering that they are literally star-crossed: Her planet, Landfall, has been locked in a bloody, decades-long war with Wreath, Landfall’s moon and his home. Each has been raised to hate the other side, from their clashing ideologies to their physical differences (his horns, her wings); they meet as guard (her) and prisoner (him) in a prison camp on the Planet Cleave. But it’s not Marko speaking the Landfall Language instead of his native Blue that binds them; it’s their “Secret Book Club,” where Alana reads aloud passages from her favorite romance novel during their work shifts. A Night Time Smoke, D. Oswald Heist’s tale of the love between a man made of rock and the quarry owner’s daughter, so radically shifts both of their perspectives that they are able, for the first time, to meet in the middle.

It’s no surprise that soldiers Marko and Alana fall in love over a romance novel, considering that they are literally star-crossed: Her planet, Landfall, has been locked in a bloody, decades-long war with Wreath, Landfall’s moon and his home. Each has been raised to hate the other side, from their clashing ideologies to their physical differences (his horns, her wings); they meet as guard (her) and prisoner (him) in a prison camp on the Planet Cleave. But it’s not Marko speaking the Landfall Language instead of his native Blue that binds them; it’s their “Secret Book Club,” where Alana reads aloud passages from her favorite romance novel during their work shifts. A Night Time Smoke, D. Oswald Heist’s tale of the love between a man made of rock and the quarry owner’s daughter, so radically shifts both of their perspectives that they are able, for the first time, to meet in the middle.

With this newfound connection, Alana can’t bear to send Marko to Blacksite, from which he may never return, so she frees him and goes on the run with him. All this only twelve hours after meeting him! While it’s not a particular tongue that unites them, it is a shared language.

It’s actually called the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, after linguist Benjamin Lee Whorf.

I loved Babel 17 as a youth! I especially liked the ghosts as the sensors on the ship, and Delaney’s body modifications (who wouldn’t choose a 3D dragon in a cage over a dragon tattoo) but the peculiarities of Babel 17 went over my head I’m afraid.

@1: Thanks for pointing out the typo! As much as I’d love to visit a wharf that celebrates language, I want to make sure that Benjamin Lee Whorf gets the proper credit. :)

@3: A wharf that celebrates language sounds great! I almost regret correcting you.

To add to the “Little Mermaid” description – in the stage show, this is taken even further. When Ariel first comes to the castle, Eric tries to make her feel more at ease by teaching her how to dance. Later, Grimsby talks Eric into holding a singing contest as his last attempt to find the mysterious singing woman who saved him. Three candidates sing unsuccessfully, then Ariel comes in, and Eric understands that she wants to dance for him. She dances, and he chooses her rather than continue to chase his mystery woman – and then Ursula shows up to declare the sun has set.

I was thinking if I could remember something to add and one of the first things I came up with was “Tarzan”. I hate all these clichés with Tarzan pounding on his chest uttering “Me – Tarzan, you – Jane!”; instead, I am talking about the original novel written by Burroughs where Tarzan has not yet learned to speak in human languages (though, admittedly, he has taught himself to write in English, but he does not have anything to write on before she is safely back with her friends and therefore she doesn’t know the love letter slipped in from under her door before being rescued from Africa is from him. She learns it when they meet again in America after he’s learned to speak in English and French). During their first couple of days together, they fall in love with each other while only communicating through gestures and actions and it’s a love that only gets stronger through the years.

The same kind of happens when their son Jack/Korak rescues a girl Meriem. Even though they fall in love when grownups, they still start out without understanding each other’s languages, so the bond they initially form between each other starts without words.

@@.-@ Somebody should just name a wharf after Whorf.

I love that Little Mermaid is on here…and I always did find it kind of sweet that, without Ursula’s interference, Eric really was falling in love with Ariel for who she was, not just waiting for some idealized fantasy woman.

Trying to think of others to contribute; maybe Siri/Susebron in Warbreaker counts, although IIRC it wasn’t that he didn’t understand the language but that he couldn’t read/write (or talk).

The movie Happy Feet is not great, but I loved how it used dance as a language in the end. It had ramifications for how we might communicate with aliens, not with sounds, but with movement.

Bruce Sterling’s charming 2002 short story “In Paradise” deals with an American man and an Iranian woman who fall in love at first sight (at an airport) and run away together while never learning each other’s language; they communicate via the translation app on her smart phone. (Which is apparently pretty good — at one point she enthuses, “You must be a famous poet, for you speak such wonderful Farsi.”)

STARDANCE by Spider and Jeanne Robinson eventually uses dance to communicate with aliens. And then there’s the Suzette Haden Elgin books about Nazareth and alien linguistics, and her novel COMMUNIPATH. Hey, never get in the way of a PhD in linguistics when she’s writing science fiction…